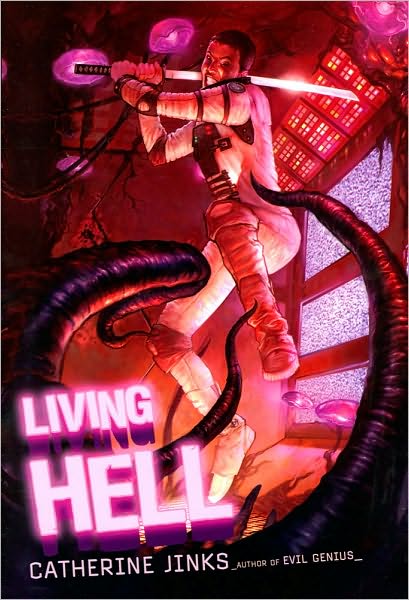

Living Hell, by Catherine Jinks

Apr 27

2010

Great horror novels usually feature two things: a terrifying antagonist and a plot capable of lending weight to what would otherwise just be a lot of running and screaming. Catherine Jinks' novel Living Hell is weak on the plot front, but her villain was so memorable that it took us a while to notice.

Living Hell is narrated by 17-year-old Cheney, a second-generation inhabitant of the Plexus, a self-contained spacecraft searching for a habitable planet. The Plexus is designed to promote humanity's survival, but when the ship drifts through a bizarre cloud of energy, its mechanical elements begin transforming into organic ones. As the ship changes into a living thing, it begins to identify the humans living inside it as alien organisms—organisms that need to be eliminated.

We had several technical complaints about Living Hell: it was too short, it would have worked better as a series, it featured an implausible collection of survivors, etc. (Plus, the central plot conceit strained credulity, but the popularity of Lost proves that Americans can overlook a lot of credulity-straining.) However, none of these thoughts registered until after we'd closed the book. While we were actually reading, all we were thinking about was how SUPER CREEPY the "ship as a human body" metaphor was. We've seen scarier villains than a sentient spaceship (read: clowns), but not many, and definitely none as the Big Bad in a kids' book.

Living Hell is narrated by 17-year-old Cheney, a second-generation inhabitant of the Plexus, a self-contained spacecraft searching for a habitable planet. The Plexus is designed to promote humanity's survival, but when the ship drifts through a bizarre cloud of energy, its mechanical elements begin transforming into organic ones. As the ship changes into a living thing, it begins to identify the humans living inside it as alien organisms—organisms that need to be eliminated.

We had several technical complaints about Living Hell: it was too short, it would have worked better as a series, it featured an implausible collection of survivors, etc. (Plus, the central plot conceit strained credulity, but the popularity of Lost proves that Americans can overlook a lot of credulity-straining.) However, none of these thoughts registered until after we'd closed the book. While we were actually reading, all we were thinking about was how SUPER CREEPY the "ship as a human body" metaphor was. We've seen scarier villains than a sentient spaceship (read: clowns), but not many, and definitely none as the Big Bad in a kids' book.

Posted by: Julianka

No new comments are allowed on this post.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!