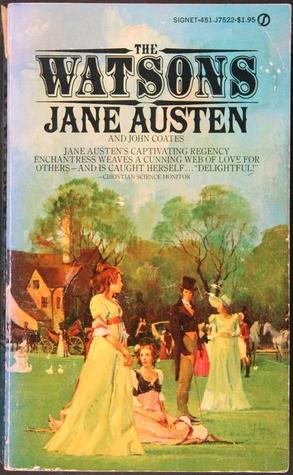

The Watsons, by Jane Austen and John Coates

Mar 14

2016

Sometime between 1803 and 1805, Jane Austen wrote the first five chapters of a novel called The Watsons. The story opens on a grim note: a young woman named Emma Watson returns to her family after spending many years in the care of a widowed and wealthy aunt. When her aunt makes a foolish second marriage, Emma is shipped off to her father's house, where she joins her three older sisters. Emma has two brothers, a surgeon and a lawyer, but none of her sisters have married, and their father is both poor and physically fragile. While Austen leavens this gloomy depiction with plenty of her trademark wit and barbed commentary, she makes it clear that Emma and her sisters are dangerously close to slipping from genteel poverty to genuine poverty.

Austen eventually set The Watsons aside, but the tantalizing fragment she left behind has inspired several authors to transform it into a full-length novel. Among them was John Coates, a professional author and playwright who published a continuation of The Watsons in 1958. I have a lot of complaints about the final product (brace yourselves, dear readers; they're coming), but to do Mr. Coates justice, his plot is coherent, his dialogue and characterization show flashes of genuine wit, and his writing style is mostly free from obvious anachronisms. To be blunt, I've read far worse Austen continuations and retellings—Coates's The Watsons is better than this. Or this. Or, Lord knows, this.

Sadly, Coates's writing skills are wholly overshadowed by his inability to capture Austen's tone. In a note at the end of the novel, he mentions that he wanted to avoid turning his heroine (whom he re-names Emily) into another Fanny Price. He certainly succeeded—instead of resembling shy, self-effacing Fanny Price, Emily is a dead ringer for Mary Bennet: a sanctimonious, moralizing prig. Check out this representative scene, in which Emily decides to intervene in an interaction between her sisters, Penelope and Margaret:

When Emily isn't criticizing her siblings' morals, manners, and life choices, she is prone to statements that drip with Mr. Collins-style false humility. I think we're supposed to take lines like these as proof of her demure nature, but they mostly make me want to slap her:

Coates's afterword includes a disclaimer: his book is not for the kind of Austen fan who believes “Jane Austen is above criticism of any kind and even her fragments are sacrosanct.” I don't know if I'd go that far (although I probably would), but I do feel that even Austen's fragments deserve a co-author who attempts to capture her fundamental world view. Judged by that standard, Coates's The Watsons is a failure, and nothing else about this technically competent continuation is interesting enough to make up for it.

Austen eventually set The Watsons aside, but the tantalizing fragment she left behind has inspired several authors to transform it into a full-length novel. Among them was John Coates, a professional author and playwright who published a continuation of The Watsons in 1958. I have a lot of complaints about the final product (brace yourselves, dear readers; they're coming), but to do Mr. Coates justice, his plot is coherent, his dialogue and characterization show flashes of genuine wit, and his writing style is mostly free from obvious anachronisms. To be blunt, I've read far worse Austen continuations and retellings—Coates's The Watsons is better than this. Or this. Or, Lord knows, this.

Sadly, Coates's writing skills are wholly overshadowed by his inability to capture Austen's tone. In a note at the end of the novel, he mentions that he wanted to avoid turning his heroine (whom he re-names Emily) into another Fanny Price. He certainly succeeded—instead of resembling shy, self-effacing Fanny Price, Emily is a dead ringer for Mary Bennet: a sanctimonious, moralizing prig. Check out this representative scene, in which Emily decides to intervene in an interaction between her sisters, Penelope and Margaret:

Penelope's arrival had made for a increasing bustle in the house; and though she enjoyed her new sister's company, Emily was glad of an occasional evening's quiet conversation or silent reflection in her father's book-room. Further acquaintance had taught her more about Penelope's character. There was no deceit in it; but a good deal of thoughtlessness. Margaret was often provoking. Her artificiality, her false sentiment, and her readiness to feel slighted, laid her open to teasing; but Emily sometimes wished Penelope would show a little restraint with her wit. She resolved, when the opportunity offered, to speak with her on the subject.Bear in mind, Emily is both the youngest member of the family and almost totally unknown to her sisters. While Jane Austen continuously emphasized the value of delicacy, Coates seems to have no idea that his heroine's unsolicited advice on correct behavior might be seen as presumptuous. On the contrary, he depicts it as useful and kindly meant. (One can only assume he had no sisters of his own.)

When Emily isn't criticizing her siblings' morals, manners, and life choices, she is prone to statements that drip with Mr. Collins-style false humility. I think we're supposed to take lines like these as proof of her demure nature, but they mostly make me want to slap her:

“I trust,” said Emily, “my being of my aunt's household will not detract from the pleasure of your visit.”His pontificating heroine isn't the only example of Coates's moral tin ear. He also expects us to sympathize with the plight of Tom Musgrave, a shallow, social-climbing flirt who ends up married to Emily's shrewish sister Margaret. Seeing as Tom only proposes to Margaret because he incorrectly assumes she is about to become the sister-in-law of a wealthy lord, I viewed her nasty temper as his just desserts. Coates, on the other hand, clearly sees Tom as a flawed but pitiable character sadly disappointed in his marriage—a diet version of Mr. Willoughby.

Coates's afterword includes a disclaimer: his book is not for the kind of Austen fan who believes “Jane Austen is above criticism of any kind and even her fragments are sacrosanct.” I don't know if I'd go that far (although I probably would), but I do feel that even Austen's fragments deserve a co-author who attempts to capture her fundamental world view. Judged by that standard, Coates's The Watsons is a failure, and nothing else about this technically competent continuation is interesting enough to make up for it.

Posted by: Julianka

No new comments are allowed on this post.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!