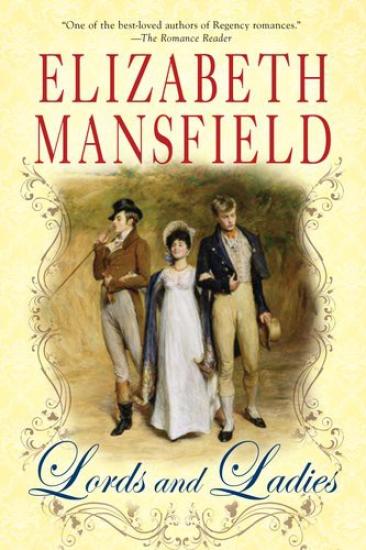

Lords and Ladies, by Elizabeth Mansfield

May 11

2012

As I read Lords and Ladies, a recently-released omnibus edition of three of Elizabeth Mansfield's Regency-era romance novels, one thought remained paramount throughout: I have got to learn more about copyright law. Because while I found the first two stories featured in the collection silly and far-fetched, the third was a shameless rip-off of Georgette Heyer's A Civil Contract*, minus all of the plot elements that made A Civil Contract so intriguing.

Lords and Ladies collects Mansfield's 1979 novel A Very Dutiful Daughter, 1982's The Counterfeit Husband, and 1989's The Bartered Bride into one volume. A Very Dutiful Daughter is the story of Miss Letitia Glendenning, a shy debutante who stuns her family by refusing to marry London's most eligible bachelor—despite the fact that she is all-too-clearly in love with him. Camilla, the widowed heroine of The Counterfeit Husband, enlists her suspiciously gentlemanly new footman to play the role of her husband when her overbearing sister-in-law comes for a visit, but soon finds herself wishing the deception was reality. Both stories required significant suspension of disbelief (particularly when the heroines made implausible about-faces from extreme passivity to extreme activity), but I found them readable enough... unlike The Bartered Bride, which left me brimful of irritation.

I reviewed Heyer's A Civil Contract several years ago, so if you'd like to read a more in-depth summary click here. The similarities between it and The Bartered Bride are obvious: both stories feature socially awkward heroines who are the sole heiresses to nouveau riche fortunes. Both women marry suddenly-impoverished noblemen who are already in love with other women, but forced to settle for a rich bride in order to support their families. Both heroines exhibit a gift for making their new homes comfortable, and both heroes' families eventually realize the worth of their new female relative.

I could list a dozen more similarities, but I was more interested in what made the stories different. Mansfield's hero pines for his lost love, but he finds his pretty wife increasingly attractive, and his promise not to sleep with her until she is comfortable with the relationship adds some sexual tension to their interactions. Although nothing is explicitly described, it's clear that Heyer's protagonists begin having sex immediately after marriage—although one suspects it's not particularly good sex, as the hero is grateful for his new wife's “prosaic attitude” in response to various “awkward moments” during their honeymoon. Mansfield's book therefore fits the mold of a conventional romance novel: the hero is more sexually attracted than emotionally involved for a large portion of the story, and the “happily ever after” ending is achieved by his discovery that he both loves and lusts after his wife. In Heyer's book, on the other hand, the hero is never ardently attracted to the heroine (who is quite plain, particularly in comparison to his ethereal first love), but eventually discovers that he genuinely loves her—without, however, experiencing any of the uncritical passion he felt during his earlier relationship.

Mansfield, who died in 2003, made no secret of her familiarity with Heyer's work, or the fact that she found Heyer to be both anti-Semitic and “a dreadful snob”. These accusations were quite true, although unfortunately not unique; many English writers from Heyer's class and time shared these prejudices. I was taken aback, therefore, by Mansfield's description of Heyer's books as the “lightest of light reading”. While I would absolutely agree that the majority of Heyer's work was delightfully frothy, A Civil Contract is an exception—a fascinating example of a purposefully unromantic love story. The Bartered Bride steals Heyer's plot and dulls every sharp edge, transforming it into something infinitely “lighter” and more generic. This made me doubly surprised the book found a new publisher, because even if one sets aside the naked theft from a superior author, Mansfield's story simply isn't very good.

*With one vital scene from Heyer's The Grand Sophy tossed in. +5 plagiarism points, Ms. Mansfield.

Lords and Ladies collects Mansfield's 1979 novel A Very Dutiful Daughter, 1982's The Counterfeit Husband, and 1989's The Bartered Bride into one volume. A Very Dutiful Daughter is the story of Miss Letitia Glendenning, a shy debutante who stuns her family by refusing to marry London's most eligible bachelor—despite the fact that she is all-too-clearly in love with him. Camilla, the widowed heroine of The Counterfeit Husband, enlists her suspiciously gentlemanly new footman to play the role of her husband when her overbearing sister-in-law comes for a visit, but soon finds herself wishing the deception was reality. Both stories required significant suspension of disbelief (particularly when the heroines made implausible about-faces from extreme passivity to extreme activity), but I found them readable enough... unlike The Bartered Bride, which left me brimful of irritation.

I reviewed Heyer's A Civil Contract several years ago, so if you'd like to read a more in-depth summary click here. The similarities between it and The Bartered Bride are obvious: both stories feature socially awkward heroines who are the sole heiresses to nouveau riche fortunes. Both women marry suddenly-impoverished noblemen who are already in love with other women, but forced to settle for a rich bride in order to support their families. Both heroines exhibit a gift for making their new homes comfortable, and both heroes' families eventually realize the worth of their new female relative.

I could list a dozen more similarities, but I was more interested in what made the stories different. Mansfield's hero pines for his lost love, but he finds his pretty wife increasingly attractive, and his promise not to sleep with her until she is comfortable with the relationship adds some sexual tension to their interactions. Although nothing is explicitly described, it's clear that Heyer's protagonists begin having sex immediately after marriage—although one suspects it's not particularly good sex, as the hero is grateful for his new wife's “prosaic attitude” in response to various “awkward moments” during their honeymoon. Mansfield's book therefore fits the mold of a conventional romance novel: the hero is more sexually attracted than emotionally involved for a large portion of the story, and the “happily ever after” ending is achieved by his discovery that he both loves and lusts after his wife. In Heyer's book, on the other hand, the hero is never ardently attracted to the heroine (who is quite plain, particularly in comparison to his ethereal first love), but eventually discovers that he genuinely loves her—without, however, experiencing any of the uncritical passion he felt during his earlier relationship.

Mansfield, who died in 2003, made no secret of her familiarity with Heyer's work, or the fact that she found Heyer to be both anti-Semitic and “a dreadful snob”. These accusations were quite true, although unfortunately not unique; many English writers from Heyer's class and time shared these prejudices. I was taken aback, therefore, by Mansfield's description of Heyer's books as the “lightest of light reading”. While I would absolutely agree that the majority of Heyer's work was delightfully frothy, A Civil Contract is an exception—a fascinating example of a purposefully unromantic love story. The Bartered Bride steals Heyer's plot and dulls every sharp edge, transforming it into something infinitely “lighter” and more generic. This made me doubly surprised the book found a new publisher, because even if one sets aside the naked theft from a superior author, Mansfield's story simply isn't very good.

*With one vital scene from Heyer's The Grand Sophy tossed in. +5 plagiarism points, Ms. Mansfield.

Posted by: Julianka

No new comments are allowed on this post.

Comments

SR

I read Lords & Ladies recently and was amazed that there could be such a blatant copy of "A Civil Contract".I believe that when Georgette Heyer was alive she sued Barbara Cartland who had lifted parts of her books. I never saw signs of Anti -semitism Ms Mansfield writes of in Heyers books,there are references to "going to the Jews" to borrow money as an unpleasant last resort but that is an 18th century expression.Actually Elizabeth Mansfield and Barbara Cartland were not the only writers of Regency romances who used Georgette Heyer's research,lifting expressions often not quite `a propos. M Balogh writes a great deal about the Regency period rather repeticiously without Heyer's plots but again I think she has mined Heyer's books rather than doing the sort of detailed research into the late Georgian period that Georgette Heyer was noted for. SR

Julia

Yeah, such a blatant rip-off was actually embarrassing to read. A few years ago I got into a little tangle with a writer who had written an article for the New York Times that contained some major inaccuracies about a famous romance novel. She clearly didn't think there would be a crossover between Times readers and romance fans, or if there were, the romance readers would prove to be a totally uncritical audience. I suspect that's what happened with Mansfield's book--she just figured no one would notice her theft from another author, or care much if they did.